|

A Conversation With Nick Schade

By Peter Jones

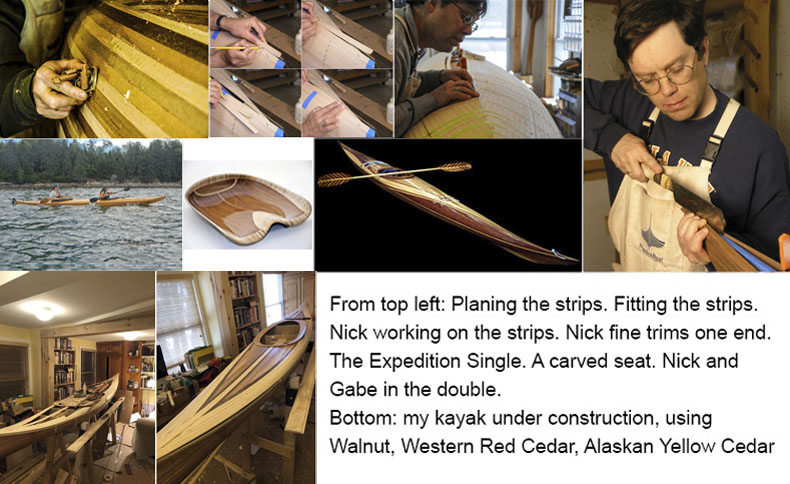

Nick Schade of Guillemot Kayaks, who specializes in building kayaks, canoes, and small boats, is one of the most well-known and influential wooden boat designer-builders on the East Coast. Nick teaches classes on small boat building and is also a kayaking instructor. His strip-built and stitch-and-glue designs have been used to build thousands of small boats over the past 25 or so years, and through his classes, website, and videos he has inspired many hundreds of do-it-yourself kayak builders to build their own boat with little or no experience. The night before the Presidential election I sat down — virtually — with Nick to find out more. I had just bought one of his kayak kits and I wanted to know what inspires him, how he designs a kayak when there already are so many kayak designs already out there, how his boats perform on the water, etc. I had lots of other questions too.

PJ: Nice to talk with you, Nick. I was really pleased when Tamsin Venn thought it a good idea to chat with you. So what got you into kayaking and kayak building?

NS: My father's idea on the weekend was to put a canoe on the roof of the car and go for a paddle. When I was around nine or ten years old he bought a kit for a skin-on-frame canvas kayak. Then I bought a fiberglass kayak when I was in high school. I envisioned doing white water paddling but I found I enjoyed paddling more on the ocean. At the time I was also reading articles on sea kayak design in "Small Boat Journal" magazine by authors like Dave Getchell Sr. When I kayaked from Some Sound to Southwest Harbor in my kayak and I realized I didn't have the right boat I decided I needed a sea kayak. After I graduated from college I drew up a plan for a sea kayak on my parents' floor and I built my first kayak. That was in 1986. I paddled that boat for a number of years until I outgrew it — it was actually too long and too stable. So I decided to design more kayaks.

PJ: I imagine you had a design or engineering background before you got into boat design.

NS: I have a background in electrical engineering and after college I worked as a civilian for the Navy at the Naval Underwater Systems Center in New London, Conn. They had a good library and I read lots of naval architecture texts. So all my design knowledge is self-taught. Woodworking I picked up from working in my dad's shop.

PJ: You're a boat builder, a designer, you teach boat building classes and you're a kayaking instructor/coach. How do you find time for it all and what's gives you the most satisfaction?

NS: I think what got me into this in the first place was simply a love of being out on the water. Designing and building was, in the beginning, done out of sheer frugality. Since my childhood, I've always liked making things. I like using CAD (computer-aided design) and I love that I can come up with a design, and then in the shop I can fit pieces of wood together with epoxy and fiberglass. I like working on my website and lately when I'm trying out new designs I try to follow the things that interest me, to design boats that I like and I hope that people will like them too. But in the end, I just love being on water. This is my motivation.

PJ: It must have been quite of a leap of faith to switch careers and go into boat building full time.

NS: Yes, I was employed by the navy as an electrical engineer working in low frequency electromagnetics for about nine years and I took a severance package when my department in New London reorganized in 1996. At that point I'd already been selling kayak plans for a few years and I'd written my first book, "The Strip-Built Sea Kayak". I like getting people interested in building boats — do-it-yourself boat builders relate to this stuff and building a boat can be a life-changing experience. I also build custom boats but I must charge quite a lot to make that side of the business work. I've also built a boat which is a permanent exhibit at MoMA. However, I really don't consider myself a woodworker — I just happen to enjoy building kayaks in wood.

PJ: Can you tell me something about your company Guillemot Kayaks and the successful partnership you have with Chesapeake Light Craft?

NS: I started Guillemot Kayaks in 1993 which was when I put my first ad for my designs in "Messing About in Boats" magazine. By 1995 I was working with Newfound Woodworks and they made the kits from my designs. Around that time I met John Harris, Managing Director at Chesapeake Light Craft at a Wooden Boat Magazine photoshoot. We hit it off, both personally and from a business standpoint, and John was able to market my designs and kits effectively so I started to sell my designs through Chesapeake Light Craft. It was a good move, a good business decision to move over from Newfound Woodworks to Chesapeake Light Craft. They have a fairly large footprint in the kits and plans business and have the resources, for example, for me to do demo days at boat shows and to market my plans and kits. So it's been a good way to get my designs out there and it has worked out well for both sides.

PJ: It seems to me that the number of people building their own kayaks started to take off twenty or twenty-five years ago and that number has increased steadily since then. Was that because at that time materials and methods for building with fiberglass had been perfected and also people were then looking back to more traditional materials like wood? Could you talk us through that era from a design and a materials point of view?

NS: There were a number of things going on at the same time. Fiberglass fabric hadn't changed that much, but in the early nineties, MAS Epoxys started to produce epoxys that didn't blush (Note: blushing is a chemical reaction during the curing of epoxy which resulting in a waxy film that rises to the surface of the epoxy matrix due to changes in humidity). Blushing is a problem if you want to build bright finish boats. Other epoxys like West System's was good for wood bonding but it tended to be thicker and harder to work with and could blush internally. MAS epoxy is low blush and has a low viscosity, and also soaks well into wood which makes building boats much easier. MAS Epoxys and Chesapeake Light Craft happened to be in the same building so they both benefited from each other.

I started my design business around that time. Pygmy Boats started a little earlier and the book "CanoeCraft" by Ted Moores, the first definitive book on strip building, came out in the early 80s. I built a canoe with my brother in 1983 from Gil Gilpatrick's book ("Building a Strip Canoe"). More people were beginning to make strip-built sea kayaks through the late 80s into the early 90s. Then there was the internet appearing on the scene. I started my website in 1994, quite early on at the beginning of the internet. I found it was a good way to connect with a diffuse group of people who were interested in kayak building. Traffic peaked on my bulletin board in 2005 for kayak builders building traditional skin-on-frame/strip-built/stitch-and-glue Greenland style kayaks. Interest also speeded up due to the changing demographics: There were more baby boomers who were becoming interested in building their own kayaks.

PJ: You've spent the last 30 or so years around wooden kayaks. Is the attraction that people have for wooden kayaks all about building their own boat? Aside from their obvious visual appeal is there some on-the-water advantage that wood has over other materials? Or is it more about the timelessness, the mystique of building and paddling with wood?

NS: The majority of builders building from my plans are not serious kayakers but are recreational kayakers who are also woodworkers. They are asking themselves, "what new woodworking project can I do?" Building a boat is the ultimate woodworking project. Traditional lapstrake boat building is significantly more involved and out of reach for a lot of people. But strip and stitch-and-glue building involves relatively minimal woodworking skills and it's pretty accessible for basic boat builders. And you end up with this beautiful, graceful craft with a lot of visual appeal. Fiberglass kayaks are relatively heavy compared to a wooden-fiberglass boat which is lightweight, strong, and responsive on the water. You can get addicted to building these boats.

PJ: Without giving anything away, what's next for Guillemot Kayaks?

NS: I'm interested in bringing in plans by other designers to my online catalog, for example Ted Moores and Joan Barrett of Bare Mountain Boats have some exceptional designs of canoes as well as kayaks and I'd like to expose my customers to these since I don't have that many canoe designs right now. Steve Killing is a naval architect who I would like to work with, and I can bring in other designers too. Having these designs for the future mean a lot to me and it could be a good business move. I also have some ideas for new designs myself and I'd like to showcase these in the catalog. I'll continue to build custom boats but I foresee this side of the business becoming less important.

PJ: On your website you have 30 or so designs for strip built and stitch and glue and kayaks. Can you estimate how many kayaks have been built using your designs?

NS: That's hard to say because when I send off plans I don't generally hear back from my customers. Also there are articles and the book and I don't know how many are built from plans in articles and in my book. It's in the thousands, but I have no record of the exact number.

PJ: You have some pretty sophisticated graphics on some of your videos which show cross sections and profiles of boats and images which you can visualize in 3D. Could you briefly walk us through your design process. For example, how do you go about using software to optimize hull shape for speed and maneuverability?

NS: The first stage of designing is to be on the water along waves and surf, etc., looking at the performance and characteristics of your boat, and you can also be looking at other boats under the same conditions. Then I ask myself, how can I make this boat perform better in those specific conditions? Basically at this point I might already have a design that I'd like to improve. So I modify that design using 3D CAD where I can treat a digital model like a piece of clay. The software allows you to visualize the model in three dimensions by slowly spinning it.

After visualization, you can drop that information from that model into a drag analysis program to analyze the degree of drag. I then use a drag predictive algorithm which mutates the design randomly. I can produce a whole family of designs from which I can pick the best, and after perhaps thousands of iterations I can optimize for low drag, then put in parameters like boat width and stability which will give me a hull shape. Then the program will construct the deck or, alternatively, I can take an existing design for a deck which will give the best performance.

So I tend to adopt a design spiral approach which consists of iterations through a sequence of design tasks from an idea of a shape, with each iteration refining the boat to the next stage of design optimized for specific conditions on the water. For example, you might optimize for speed, or for carrying gear.

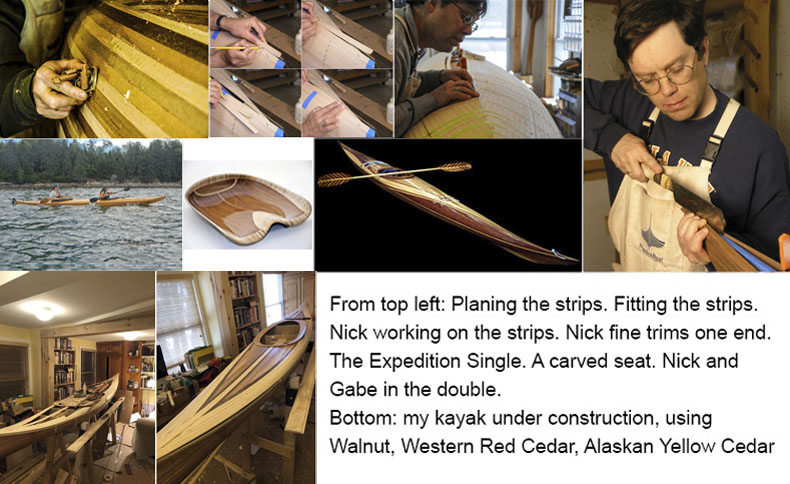

PJ: Can you tell me something about the different woods you've used over the years.

NS: Western red cedar is the go-to wood for strip building. It's easy to glue, accepts epoxy well and it's a beautiful looking wood. It has a high strength-to-weight ratio, is readily available, has a straight grain with no knots and comes in long lengths — one 20-foot, 1.5 by 12 board is enough to build a strip-built kayak. I've used ebony, mahogany and maple and each has its peculiarities. Paulonia and Okoume are both used for building stitch-and-glue kayaks.

PJ: What about specialty tools? I have a really nice Japanese saw and I'm thinking of buying a Japanese plane to build my kayak.

NS: A primary tool is a good table saw if you are cutting wood for strips. For planing and trimming I use a simple block plane and a jack-knife given to me by my grandmother. Also a Japanese pull saw and a pair of loppers or anvil cutters. Good tools, like a Lie-Nielson block plane or a Stanley low angle block plane are nice to use but I have a perfectly good block plane that cost just $8. Everybody likes collecting good tools but I want people to understand that you don't need fancy tools. On the other hand, well-made tools are much nicer to work with. One of my goals at some point is to make a video where I show you can build a kayak with just the basic tools.

PJ: My next question, and I think I know the answer, is."What is your favorite boat?" I think the answer might be the one that does the best in the conditions you find yourself.

NS: At this point I'm actually paddling a fiberglass Petrel Play kayak. A friend is producing a composite version of the Petrel Play and I've been paddling that a lot to learn how it's doing on the water. Petrel or Petrel Play are my go-to boats and I prefer strip-built because I like the aesthetics. I do my best to get my stitch-and-glue Petrel to perform as well as the strip-built.

PJ: The first of your models I heard about was the Guillemot. What are its characteristics on the water and what came next after the Guillemot?

NS: The Guillemot was actually the third line of boats. The Great Auk was the first boat. The Great Auk tracked a little stiffly and for some people it tended to turn once you stopped paddling. The Guillemot was a reaction to the design of the Auk,. It's a little more playful than the Great Auk and does well when the boat is moving and it's a well-balanced boat. But there were some difficulties in building the Guillemot so I changed the shape slightly which made it easier to build. I later wanted something longer and faster, so that led to the Night Heron. The Petrel was the next iteration and it fitted the performance I was trying to get when I designed the Guillemot. In the Petrel Play I went after a design for a shorter, high performance open-water kayak.

PJ: I know the Petrel Play is maneuverable in surf and is also as fast as much longer sea kayaks. What was your thinking behind the design for the Petrel Play?

NS: In the early days when I thought of sea kayaking I thought of expedition touring, a trip you'd take, for example, on the Maine Island Trail. But in reality, most people need an expedition touring boat for, say, just one week a year. The rest of the year they probably don't need a 19-foot boat. And for myself, just playing in tide races, a shorter boat performs better. First I did a stitch-and-glue Petrel, then a Petrel Play stitch-and-glue, then I built a strip-built Petrel Play. The Petrel Play is a performance boat and can also be used for recreational paddling — it's a crossover.

PJ: My penultimate question: I have a vague idea of the mechanics of weathercocking, the turning of long narrow boats into the wind. I'd be really interested to hear, as a boat designer, your explanation for the dynamics of weathercocking.

NS: Yes, I've been using an explanation I got from Ken Fink: When the kayak goes forward there is a high pressure on both sides at the front surfaces and a low pressure on the back surfaces of the boat. In a beam wind, there's high pressure on the leeward side in the front and a low pressure on the windward side in the front. Conversely, in the back, the windward pressure is lower on the leeward side. When you add all those high pressure / low pressure systems up you'll find the boat, when it's pushed sideways, will turn into the wind. You can prevent that sideways motion with a skeg which can actually be placed in the rear or the middle of the boat to be effective.

PJ: Well, it's been great chatting, Nick. My final question for you is, for someone building their first Nick Schade-designed kayak, if you have just one piece of advice you can give, what would that be?

NS: "Just get started!" If you overanalyze, "analysis paralysis" can take over. I admit that even I sometimes still have problems getting started on a new project. For example, if you look at Step #27 in a process you may be intimidated, but Step #27 becomes more obvious once you've done the other steps. So start at Step #1 and just keep going. It's a commitment when you start. A big long task! And you're committing yourself when you take that first step. I know there are a lot of boats out there where the builder has had a minor setback and then it was hard for them to go back and start again. Strip building works well as one small step a day, it's an incremental project. You know its a big task and once you start you have a lot to do.

|